Stay in the know

Subscribe to the Real Estate Blog and we’ll send you an email each time something new is posted.

Subscribe to the Real Estate Blog and we’ll send you an email each time something new is posted.

Blogs

Real Estate Blog

10 Things Real Estate Developers and Investors Should Know About Boston Zoning and Local Permitting

Major real estate development projects like the former Filenes site downtown and the New Balance “Boston Landing” project in Brighton are clear indications private developers and investors are focusing their attention on Boston with renewed interest in large commercial and mixed use real estate development projects. Many of these developers and investors, especially those from out of state, may not be familiar with the local zoning and permitting framework applicable to their proposed projects. Below is a brief summary of just some of the issues developers and investors should consider when planning such projects in Boston that could have significant impacts on the viability of their project designs and negotiations.

1. General Framework

The first Boston building regulation and zoning act was adopted in 1924 (Chapter 488 of the Acts of 1924) and was almost immediately out of date. It included, for example, regulations of uses such as blacksmith shops and steam railroad yards. In an effort to keep the zoning code up to date with the rapidly changing landscape of the city in the 20th Century, the 1924 zoning code was repealed and replaced with the subsequent 1956 Enabling Act which serves as the authority for the current City of Boston Zoning Code (“Zoning Code”). The 1956 Enabling Act gives the Boston Zoning Commission (“Zoning Commission”) legislative authority to adopt and amend zoning regulations for the city, and also requires the Zoning Commission to consult with the Boston Redevelopment Authority (“BRA”) prior to adopting any amendments to the Zoning Code. The BRA is Boston’s primary planning and zoning agency and also serves as Boston’s urban renewal authority. The BRA coordinates citywide review of development proposals and has the authority, with mayoral support, to approve urban renewal projects. Additionally, the Enabling Act grants the Zoning Board of Appeal the authority to hear appeals of decisions by the Inspectional Services Commissioner (discussed below) and other administrative officials under the Zoning Code with regard to permit decisions and interpretations of the Zoning Code.

2. Boston Redevelopment Authority (Review of Large Projects)

As the primary planning and zoning agency, the BRA is charged with reviewing the design of real estate developments in Boston and assessing their impact on the surrounding community and the city as a whole. The procedure for this review is detailed in Article 80 of the Zoning Code. Any project which seeks to add more than 50,000 square feet to the gross floor area of a development will require Large Project Review by the BRA under Article 80B of the Zoning Code. Large project review involves an examination of the potential impacts of a project on the surrounding neighborhood. At the outset of the Article 80 review process, the mayor may appoint an Impact Advisory Group (“IAG”), consisting of neighborhood residents, businesses and community organizations from the area of the city impacted by the proposed development, to advise the BRA during the Article 80 process. The IAG must be invited to attend the project scoping sessions and must be consulted prior to execution of any cooperation agreement between the BRA and an applicant. The Large Project Review procedure consists of three public review steps: (i) the project proponent then submits a Project Notification Form (“PNF”) summarizing the project proposal and in response the BRA issues a Scoping Determination identifying the issues for review; (ii) the project proponent submits a Draft Project Impact Report (“DPIR”) which presents technical analyses of the impacts to areas identified as requiring additional review in the Scoping Determination and in response the BRA issues a Preliminary Adequacy Determination (“PAD”) which determines whether the DPIR has met the requirements stated in the Scoping Determination and identifies requirements for the final report; (iii) the project proponent submits a Final Project Impact Report (“FPIR”) and in response the BRA issues an Adequacy Determination after a public hearing and a vote of the BRA board. It should be noted, review of proposed projects under the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (“MEPA”) is somewhat analogous to Large Project Review in that it involves an examination of the potential impacts of a project and if MEPA review is required, this is typically done simultaneously with the Article 80 process.

3. Boston Landmarks Commission

Created in 1975 to protect the architectural and cultural distinctiveness of one of our country’s oldest cities, the Boston Landmarks Commission is the primary preservation agency for Boston charged with identifying and preserving historic buildings, places and neighborhoods. If a property is designated a Boston Landmark, all proposed exterior alterations need to be reviewed and approved by the Boston Landmarks Commission before a building permit is issued. With Boston’s long and rich history, it is not surprising to note there are more than 8,000 properties within the city designated as Boston Landmarks. Additionally, Article 85 of the Zoning Code grants the Boston Landmarks Commission the authority to review demolition of significant buildings and require a 90 day waiting period to review alternatives to demolition with the applicant. Article 85 does not grant the Boston Landmarks Commission the authority to prohibit demolition.

4. Planned Development Areas (“PDA”)

If developers find their proposed project is not allowed pursuant to the underlying zoning applicable to their project location, in limited cases the Zoning Code may allow for the creation of a special zoning district called a Planned Development Area or PDA as a form of zoning relief. A PDA allows the BRA to review a development plan in lieu of the underlying zoning requirements, but PDAs may only be established in specific areas of the city where they are permitted by underlying zoning and they may only be established on parcels containing an area of at least one (1) acre. For areas where PDAs are permitted, the Zoning Code provides district-specific dimensional requirements that would be applicable to a project if a PDA is created, such as maximum building height, maximum density and maximum number of dwelling units per acre, as well as district-specific impact standards such as wind and shadow effects and traffic impacts and district-specific use requirements. Generally, the creation of a PDA allows for greater project height, and density and a greater range of uses as well as other relief from the underlying zoning for such district. PDAs can be a beneficial tool for developers seeking to build projects harmonious with the surrounding neighborhood, but outside the parameters of what is permitted by right by the underlying zoning.

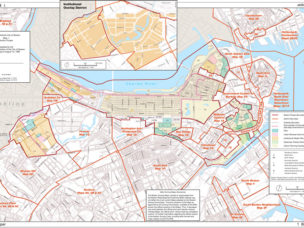

5. Boston Transportation Department (the “BTD”)

The BTD is charged with regulating traffic, parking and construction management measures in connection with large developments in Boston. Developments subject to Article 80 review will require a Transportation Access Plan Agreement (“TAPA”) between the developer and the BTD that addresses the development’s impact on the surrounding area’s transportation infrastructure and proposes possible mitigation alternatives, which may include the creation of traffic impact models, installation of traffic signal equipment, and designations of car and bicycle parking areas. The BTD also promulgates parking space guidelines throughout the city that regulate the number of parking spaces required for new developments. BTD maintains the Boston Transportation Department Parking Freeze and Restricted Parking Area Map which shows areas of Boston subject to a parking freeze. In areas where a parking freeze is in effect new commercial parking must be accompanied by the elimination of spaces at least equal to the number of new spaces being created. Construction or modification of a commercial parking facility that increases the number of parking spaces available within a parking freeze district requires a Parking Freeze Permit issued by the Air Pollution Control Commission (“APCC”). Parking freezes only apply to commercial spaces where cars are parked temporarily for a fee. Residential parking spaces are exempt from the freezes. Commercial parking facilities may be granted an exemption from the APCC upon a finding that the primary business of the owner or operator of the facility is not operation of parking facilities and that the parking facilities are only used by the lessees, employees, patrons, customers, clients patients or guests of the entity owning or operating the facility and that the public is effectively excluded from parking in the facility.

6. Public Improvement Commission (“PIC”)

If a proposal for development in Boston envisions performing work within a public roadway or public sidewalk, if the project includes a restaurant with a seasonal sidewalk café, or if an architectural feature that extends beyond the property boundary into a public right of way, the developer will need to consult with the PIC. Created in 1954, the PIC owns and regulates the city’s public rights of way, including all public roadways and sidewalks and permits are generally required from the PIC for any work performed within those public ways. The PIC also has the authority to establish the right of way lines, alter or discontinue Boston’s public ways.

7. Boston Public Works Department

The Boston Public Works Department provides engineering support to the PIC. It is the permit division of the Public Works Department that issues permits for any work performed within a public way or public street within the city if any work is to be done within a public way or if there is a need to temporarily close any such public way during project construction.

8. Boston Inspectional Services Department

The Commissioner of Inspectional Services is the city’s primary authority for administration and enforcement of the Zoning Code. A demolition permit is required from the Inspectional Services Department (“ISD”) prior to commencement of any demolition work for any development project in Boston. Additionally, a building permit is required from the ISD prior to the construction of any development. ISD cannot issue a building permit until the BRA has issued a Certificate of Consistency indicating that the proposed construction plans for the project are consistent with the Article 80 approval discussed above. Article 8 of the Zoning Code addresses uses permitted by right in particular zoning districts as well as conditional uses and forbidden uses. If a proposed use is not permitted by right in the zoning district where a development is located, in addition to other zoning relief, a developer or owner may seek relief in the form of a conditional use permit pursuant to Article 6 of the Zoning Code or possibly a variance pursuant to Article 7 of the Zoning Code. The Board of Appeal has authority to hear appeals of ISD decisions and to grant such conditional use permits and variances.

9. Affordable Housing

The BRA’s Inclusionary Development Policy (“IDP”) effective October 3, 2007 requires any project undertaken or funded by any agency of the city or developed on city property that proposes ten or more housing units to make no less than 15% of those units affordable to moderate-income and middle-income households. Additionally, any developer of private property proposing a project with ten or more housing units, and seeking relief of any kind from the Zoning Code, is required to make 15% of the units in those projects affordable to moderate and middle-income households. Additionally, the units must be comparable in size and quality to the average of all market-rate units in the development and developers will need to ensure long term affordability of these units. While the city prefers to see affordable units included on-site, the city does allow alternatives for developers. Rather than including affordable housing elements within their projects, developers can instead provide a number of affordable units off-site, at a different location, equal to 15% of the total number of on-site units in the project, or they can make a cash contribution to an affordable housing fund in an amount equal to an estimate of the development cost for each affordable unit of housing (the “Affordable Housing Cost Factor”) multiplied by 15% of the total number of units within the proposed project. Today the Affordable Housing Cost Factor stands at $200,000 per unit, but this amount has been frequently adjusted to accurately reflect the cost of development of these units and could be subject to change from time to time. Developers proposing to use one of the alternative methods of meeting the city requirements must also demonstrate a need to use such alternative and the benefit such alternative would provide to the city.

10. Article 37 Requirements

Article 37 of the Zoning Code seeks to ensure large building projects in the city are planned, designed, constructed and managed to minimize adverse environmental impacts. Developers should be aware that any proposed development project in Boston may need to be LEED certifiable under the most appropriate LEED building rating system. Actual LEED certification is not a requirement under Article 37.

The points introduced above are just some of the local zoning and permitting issues developers of large commercial and mixed use real estate development projects in Boston face. Any developer or investor interested in such projects would be wise to consult with an attorney early in the planning stages of their proposed project to assist with proper navigation of the Boston zoning and permitting process.